Andrew Marc and Dickon Neech talk exclusively to maverick South African film director Richard Stanley about his two features, post-apocalyptic visions, mystical beliefs and myriad film making struggles. (This interview originally appeared in the horror magazine Graven Images created by Dickon Neech). It’s a very, very long interview. Primarily for fans only. We wanted to really delve deep into the worlds and mind of Mr. Stanley and he was incredibly loquacious and forthcoming so we have kept the format primarily as a Q&A. This is one of, if not the, most in-depth interviews with the director about his first two features and a planned third film, H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau which he has been a fan of since childhood.

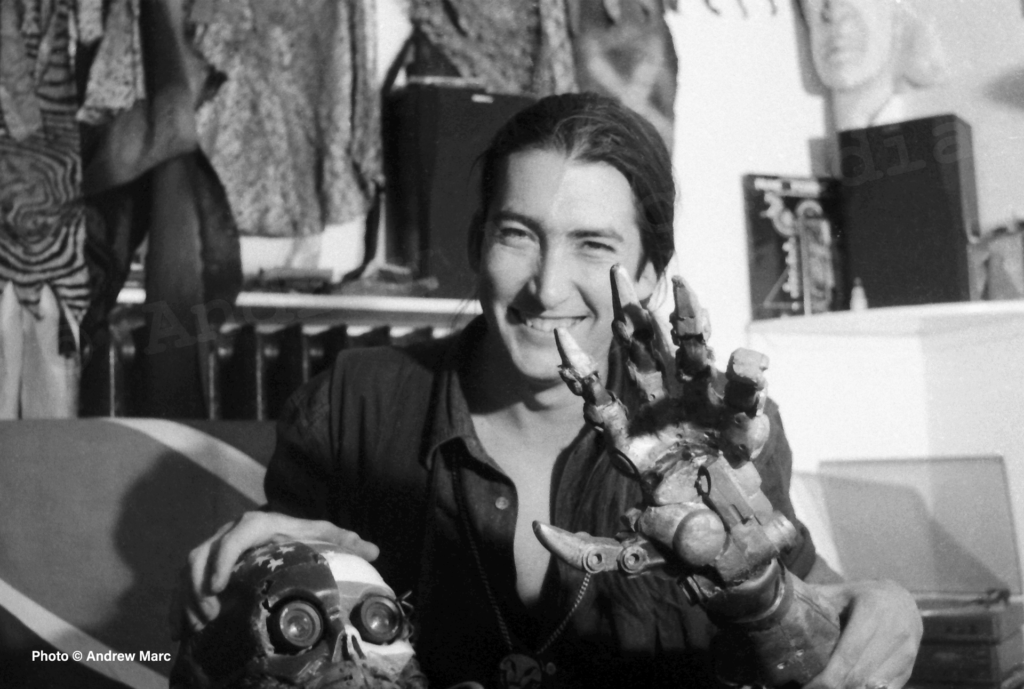

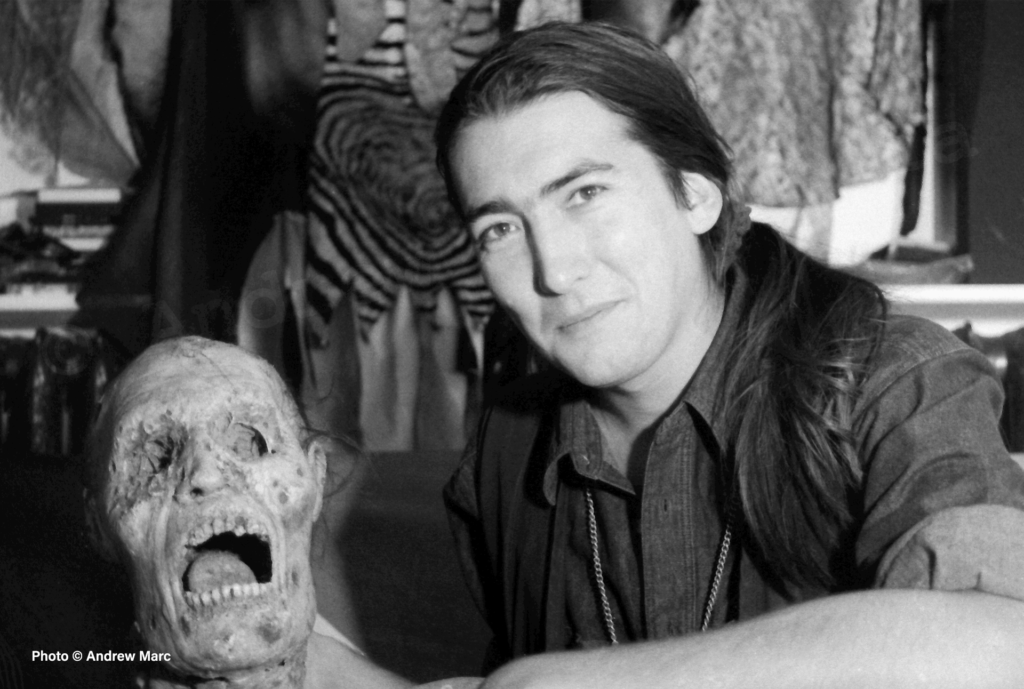

You can’t exactly plan to be a cult film director, although we get the suspicion Richard Stanley did, at least subconsciously. We are meeting him at his south London flat for a chat about his two films, Hardware and Dust Devil and his planned epic, The Island of Dr. Moreau. We managed to secure the interview with the notoriously private director after meeting him at the world premiere of Dust Devil which took place at the infamous Scala Cinema, London. The Scala, notorious for its salacious goings on, all night filmathons, audience participation and general madness, attracts auteurs from around the world who often choose to screen their latest offerings there because of the superb fan base and genuine response.

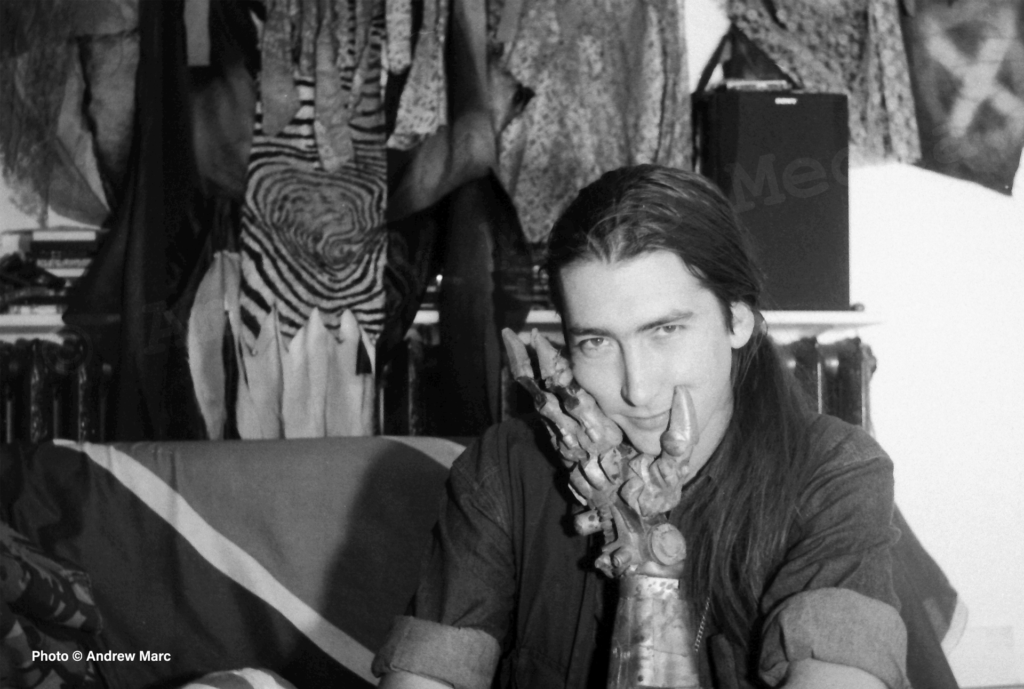

Richard answers the door, sporting a pony tail, shamanic necklace and ubiquitous spliff then we ascend the staircase to his modest abode. Immediately noticeable is the Escher stained glass window in the ceiling which has obviously been commissioned and installed. The man clearly has good taste. He is obviously all about the aesthetic, and this is more evident in his front room, which features props from music shoots, his films, film posters, and a heaving bookshelf filled with a wonderfully arcane selection of tomes – such titles as Necronomicon, most of Madame Blavatsky’s back catalogue and many other occult and mystical tomes (including, supposedly, one of the missing gospels of the bible). It’s a highly immersive and curious environment.

Richard Stanley, a native South African, is the great-great Grandson of Henry Stanley, the famous explorer known for the immortal line “Dr. Livingstone I presume?” His mother, Penny Miller, has penned perhaps the seminal book on South African occult and magic belief systems, Myths and Legends of Southern Africa, and took her young son frequently to the desert at night to explain the mysteries of the universe and give a basic shamanic induction. These strange and unusual childhood experiences have obviously rubbed off on the young Richard, who has a seriously intense air about him – indeed he has curiously described himself as a “psychic low pressure front”.

Richard studied film at the Cape Town film school, cutting his teeth on Super-8, and his student film Rites of Passage gained him an IAC International Student Film Trophy award. He also did a short called Incidents in An Expanding Universe which was to form the basis for his first feature, Hardware.

He moved to London when he was 19, desperate to escape the South African apartheid regime. In between waiter jobs and crashing on floors, he managed to get crewing work and ended up making several music videos for various artists, including Iggy Pop, Public Image Limited, Fields of The Nephilim and Renegade Soundwave, making film connections and gaining experience.

Getting bored and wanting adventure, and following a chance conversation with a crew member, he decided to do a film on the Afghan resistance to the Russian occupation plus pursue some mystical trails and legends out there. Flying to Pakistan, he then smuggled himself into Afghanistan with a clockwork 16mm Bolex camera to make the acclaimed documentary Voice of The Moon, hanging around in the Hindu Kush with the Mujahideen and just about managed to avoid getting blown up by Russian artillery. Whilst on acid.

His German cameraman Immo Horn was not so lucky and got badly injured. Both had to beat a retreat, Richard escaping with the poor crew member strapped to a donkey. Later, whilst his lensman was recovering in a Red Cross hospital, he learned his feature film script for Hardware had been green-lit, and he was to return immediately to direct. He was just 23 by this point.

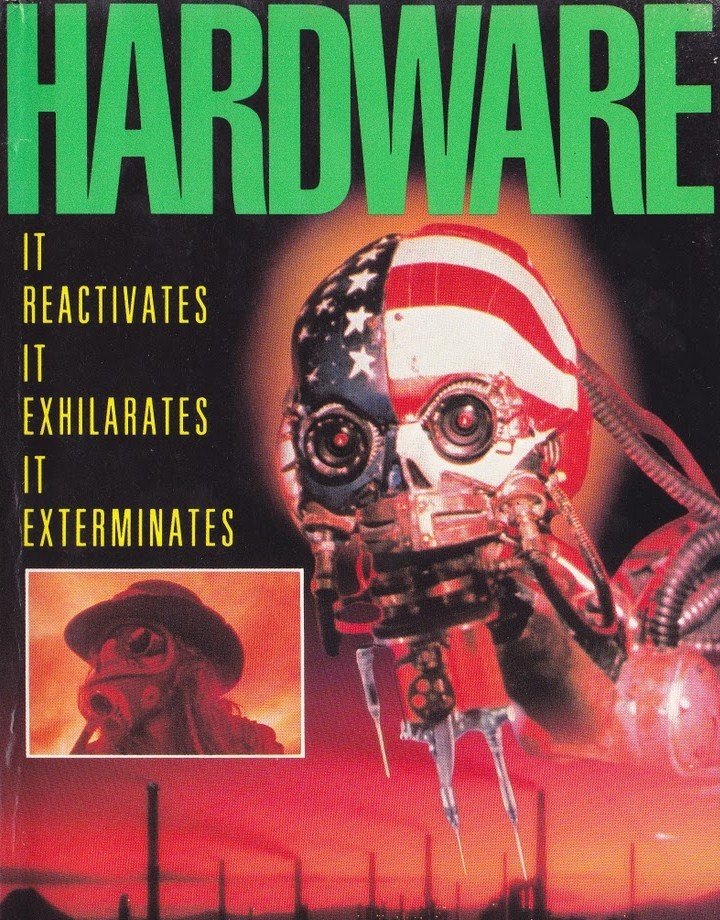

Hardware was made for the now defunct Palace Pictures, set up by Nick Powell and Steve Wooley (who also owned the afore-mentioned Scala cinema), and went on to be the highest grossing independent sci-fi horror flick of the 80’s. Following on from the financial success of his generally well received oeuvre Stanley secured funding for his second, and much more personal project, Dust Devil.

Funding came fairly easily due to the profitability of Hardware. The film was loosely based on the true life 1977 unsolved serial killings in Namibia (first dramatised in the film White Sands). It ended up being shot entirely on location in Namibia, in fact only the second ever film to be shot there following independence (the first being Dolph Lundgren’s execrable Red Scorpion).

Though superbly shot and crafted, it proved too obscure, personal and intrinsically African to secure good box office attendance. The US edit was a confused, butchered mess and it failed to make a profit, going pretty much straight to DVD. Eventually, even to get a final print made, Stanley had to front £40,000 of his own money to finance it. Very far from ideal, but at least it ensured his own director’s cut as intended. With the subsequent collapse of Palace Pictures however, distribution remained in limbo, and it failed to make a profit. Stanley’s career and indeed reputation unfortunately looks very shaky indeed at the present moment.

Undaunted by these calamities he is now pitching to make his childhood dream project, The Island of Dr. Moreau. Ever a long time fan of H.G. Wells novels, and amazingly managing to secure the rights to the story, he has started the script and fully intends to realise his updated and unsurprisingly bizarre version, in a big Hollywood remake of the 1970s version.

HARDWARE

“Hardware was primarily in desperation because nothing else I wrote was getting

made, and I wanted to write something which they definitely couldn’t say no to.”

‘Hardware was primarily in desperation because nothing else I wrote was getting made, and I wanted to write something which they definitely couldn’t say no to. So on one level, it was kind of like I thought I could make a better exploitation movie than a lot of the things I was watching, and sat down and thought “OK, if I have, you know, the chainsaw, and the baseball bat and the voyeur next door and the shower scene, the android, and the setting, the drugs and the rock and roll, and everything, they’ll give me money, and it’s set in America. On top of that, I guess it’s a personal content.

‘I was writing it in a flat in Brixton, and my girlfriend was really into metal sculpture, so there was heaps of garbage around the place always being cut up and welded. At the same time there were Chinese neighbours downstairs who I was always rowing with, so a couple of particularly bad nights things seemed to get a bit heavily out of control – windows would be smashed … people would suddenly realise that the view was better with the window broken, some of the apartment kind of grew out of the environment we were in, and it seemed to make sense to make the droid into the girl’s sculpture.

‘I think there’s also a semi-relationship to the South African business – the characters in some way reflect the problem you get in a lot of the white South Africans – they’re all kind of fairly normal, but they’re all passively supporting the system, so that the girl might be receiving welfare cheques, and the guy might actually might be working for the army, and they’re getting completely screwed by it, and eventually they get this totally out of control kind of military experiment which tears them apart but they have to acknowledge that it’s actually quite a good idea, and it’s probably a good thing that the Government’s doing it, but still get massacred (all laugh). I think there’s a little part of my memory of South Africa which overlaps into that. I think that’s about as personal as it gets, probably.’

Richard often cites revered Italian director Dario Argento as a huge influence. ‘I think that Dario’s movies were the first films that really impressed me, about their usage of rock and roll, really up-front music and up-front lighting and up-front editing all at once. Kind of completely in-your-face and the great intensity of it all, the kind of jump-cutting in on some of the items.

‘The use of hurting people, by ramming someone’s teeth into the corner of a mantle piece or stabbing someone through an unlikely place in the body like through the hand or something rather than stabbing them completely in the chest. I guess there’s also the influence of things like close-ups of Jill’s hand being cut on the broken glass as she gets pulled out of the window which is probably partially a Dario contribution.

‘The idea if something gets suddenly pulled out of the window it’s probably too big for the audience to be able to sympathise with completely, but the idea of cutting yourself on the window frame is something that they can probably make them wince a bit. So I think that it just gave me that incentive to try and make all the stunt scenes hurt a bit more than they would if one was doing a great American movie – more close-ups of feet on broken glass.’

Carl McCoy, who had a cameo as a Zone Walker, had already worked with Richard when he made several music videos for Carl’s band, Fields of The Nephilim. ‘I probably wouldn’t have put the role in if it hadn’t been for the Neff (Fields of the Nephilim) promos and working with Carl, at the same time I got together with Carl in the first place – we had a great affinity on some things, and I’ve always been very haunted and troubled by the image of the man in the hat and coat, somewhere right out there in the desert, and the first ten minutes of Hardware are in fact a dream from ages ago, and as I dreamt everything up to getting the head out of the sand.

‘I dreamt the man with the hat and coat searching around in the deep desert somewhere looking for something very frantically, then starts to dig and digging up because it was very weird sort of storm weather as well, and digging up the metal head in the sand, and then I woke up, and things like that stuck around. Carl was in chunks of Dust Devil on 16mm, there’s heaps of stuff lying around which was why we got it together to do a Neff promo in the first place. We were going down sufficiently some of the routes, but then the Neff promos just helped reinforce the whole thing and gave us a chance to try and work it out even more. It encouraged a natural tendency that way. I think there will always be a man with a hat and coat somewhere in all the movies.’

“I was trying to be as complete as possible in my use of power tool abuse …”

Hardware is pretty gory, which of course you would expect from a sci-fi horror. However, some scenes were notably sadistic, with the Mark 13 robot using its saw to carve away at a corpse, taunting the others. Why give a droid a saw we wondered, instead of, say, a gun?

‘No, that would have been too easy. We had to deal with only having one. If he was armed to the teeth no-one else would have lasted at all. We came up with the idea that the Mk. 13 that can be seen in the movie is only a mis-assembled version of the original Mk. 13, which was missing half its parts, so there’s much, much more of it.

‘The original was intended to be more spider like and probably have eight arms, and a whole sort of lower torso, and the power drill would have come out of the little bit of stomach because it was designed for clinging like a spider onto the outside of big metal hulls and cutting its way in with the power drills and stuff from its stomach, but it lost half its body, so the power drill has now become its groin area, and now its running around on what used to be its arms because the legs are missing. So that was the sort of backing concept.

‘I figured that in real life there would be tens of them and they would be fully armed, probably have flame-throwers and weaponry of some sort. They’d obviously be water-proof as well – the only reason why this one’s not water-proofed is because it’s a proto-type, and it’s just badly damaged, and that they have to be water-proof in real life. You can’t have a droid that isn’t water-proof in real life because people would figure out that all you have to do is piss on them (all laugh). That’s what Mo should have done when she (Jill) was clinging on the ledge.’

And the inclusion of the saw? It seemed rather cumbersome for a droid.

‘I was trying to be as complete as possible in my use of power tool abuse, because we had a power drill which featured prominently in the movie. We had a circular saw in the droid, and we had Stacy wielding a circular saw herself, we have a blow torch, we’ve got an oxy-acetylene torch – leaving out the chainsaw seemed like being churlish. Originally, the chainsaw scene in Hardware was much longer, and much more complicated. One of the things we had to drop to keep it in schedule was the extended death of Vernon, the younger security guard.

‘But because he was just the younger security guard, when we went down a list of things to drop from the movie, he was the character who got dropped. We had a big row over it, and I had a big row with the producer, and I broke a bone in one of my hands punching a wall over it. So we had it all ready to go – he was originally meant to be chainsawed alive, and be kicking and screaming the whole time, and the droid kept him alive to try and get the girl (Stacy Travis) to drop her guard and come on over, and he was begging for help and being cut up slowly, and it was getting really nasty.

‘It would have taken us two days to film it with all the effects necessary because there was a hell of a lot of people through the floor, you know – fake torsos and stuff like that, and eventually, we had to make two days of the schedule to get the whole ending and the shower scene filmed properly, and the thing to drop was the chainsaw scene, so it just kind of gets brandished a bit in the movie then put away again, which is a shame.’-

It would appear that for budgetary and time restrictions, the Mk. 13 cyborg was not quite as planned as often happens on lower budget productions, and was intended to be more complex.

‘The Mk. 13 is obviously a little bit of a compromise, but, probably the thing which you could compromise the most on the way it was done, is what I originally wrote in the script, I was hoping to do some of the stop-motion animation. I had an idea to do some full scale stop-motion, which was having a bolted, locked-off armature version of the droid which we could move frame by frame in real life, but marked off by half an optical, and doing a very simple split screen, and try having a full scale stop-motion droid rampaging around frame by frame formed over the course of, you know, twelve hours, or whatever, on one side of the room, and the other character reacting on the other side.

And there was the actual mechanical hand, the crawling hand, which was only written into the script for the stop-motion exercise, and then unfortunately, because of the budget and schedule, the stop-motion was dropped, so that the crawling hand was almost totally dropped as well. It was originally written as an excuse for stop motion. The other thing was, the biggest compromise on the Mk. 13 was I would have liked him to have been a been a bit smaller, but one has to have room to get everything in and out.’

One provocative inclusion in Hardware is the obscure and disturbing TV footage glimpsed occasionally. Some of it from slightly dubious sources apparently.

‘The reason we wound up with the Mondo footage is because we wanted to do a future television but at the same time, Robocop had done future television quite heavily, so we had to take an angle which Robocop didn’t take on future television; they’re putting out American cable and public access TV and things.

‘I figured that the Government were going along with Videodrome concept, the public always wanted something harder, and the idea that possibly the North American public would be watching something like Videodrome by the 21st century. I figured the way to go would be to have extremely hard TV, and also if some people are dying in the streets, it kind of got into an incredibly high crime rate, and famine, and war and stuff going on, then people aren’t going to worry about censorship anymore. It’s like no-one’s going to …… if the world is in a state of decline, then I don’t imagine that they’ll be thinking, you know, if you’re watching a cannibal movie, that it’s going to make you a killer or something. A lot of people are going to be dumped on your door step as you go out of the house. So I figured that censorship would more or less just gradually evaporate, but still leave political censorship probably, and sort of idealogical censorship but they’ll probably put S&M TV and people watching each other, it will probably be very common.

‘The Mondo footage was from an assortment of people. The main suppliers were Survival Research. The guys from San Francisco, Mark Pauline. He makes mechanical sculptures that tear each other apart and lost his hand, famously, and built himself a mechanical hand but does strange cultural shows.

‘My favourite show is The Strange And Terrible Saga Of Future Warfare (all laugh) but I figured that it’s a great sort of area which is metal sculptures attacking each other, and metal sculptures coming to life and going ape-shit which is basically in the Hardware promo, and the metal sculpture which kind of attacks the sculptress, and also somebody has lost his hand, and had to have a mechanical hand … so there’s a clip of one of his shows on the TV, which is the big mechanical cow thing with someone shoving a power tool into it’s head.

‘The other clippings come from Genesis P. Orridge and The Temple of Psychic Youth and Genesis P. Orridge did a lot of rights clearance for us in Hardware and he has an on-screen credit on the end roller, but that footage came from a private S&M tape that Genesis had made of him kind of torturing various people who had joined his fan club, and the tape became very interesting because last year they’d been having all these big exposes of Satanic child abuse and various little pieces on social workers all over Britain. No-one’s actually turned up any evidence yet of anything that looks remotely real and it always seems to be like a Salem witch hunt and kind of religious repression and things, but somebody turned up conclusive evidence of Satanic child abuse and it went out on Channel Four, a program, an expose program on the Satanic abuse thing claiming it was all true, and the footage they showed on Channel four was exactly the same sort of footage that we showed on Hardware on the TV set, which is now found as conclusive proof of what’s all going on.

‘It’s actually Genesis’ home S&M tape, but Genesis is sort of in a very bad position over it because there was also a big trial where an S&M ring was kind of done for committing sadistic acts on each other and they were all jailed for it because they proved in court that even if you were willing to have sadistic acts perpetrated on you, it’s still committing a crime, although Genesis tapes were from consenting parties, and some of his friends, they weren’t really anything to do with Satanic child abuse. He was still guilty of committing a crime, but fortunately he was on holiday at the time, and has stayed on holiday ever since, and is in America and hasn’t been able to come home. He’s still on the run.’

Pretty heavy stuff for some background clips on a TV. It struck home just how much pre-planning and research goes into a feature film, especially one as covertly layered as a Richard Stanley film. A lot of films have cultural references, but Stanley has a unique knack for sourcing from the underground. Mining subcultures. Harvesting the peripheries. It’s what makes his films stand out in many ways. One such element was some of the production design. Clearly, there are elements of a Soylent Green type dystopia for the external shots and Argento type interiors, as discussed earlier, as well as other cultural and filmic influences, much from his music videos.

Responsible for the initial concept designs was the artist Graham Humphries, who also did the Evil Dead poster art amongst other things. ‘Graham Humphries did all the original conceptual artwork, and the big colour spreads which I think helped establish the vivid colour scheme of the movie, and all the bright primaries that freak people out when it gets translated to video, and he did a lot to establish the look of the droid; ultimately, the droid was primarily down to Graham Humphries who worked it out and drew it, and sent it to Image Animation and they drew what they could do based on our version.

‘Then we said “we don’t like what you can do, maybe you can do it like this”, and sent back another drawing, and it went on for quite a while, but he had quite a big hand in the actual droid design, he also contributed the Tibetan mural on Shades’ wall and he also story boarded the whole thing. The entirety of Hardware exists in thousands of story boards, including all the bits and pieces which we never had time to shoot, and he did heaps of work story-boarding, lots of good looking design work, as well as the script, and said we could do it for under a million, and, that really got us the movie in the end, as well as a bit of skulduggery at the casting.’

We enquired as to production problems as Hardware was a pretty tough shoot, on a low budget with tight deadlines.

‘The only major problem during the filming of Hardware is that everything was too cheap, and we didn’t have enough time, so that there was a constant race against the clock. We had to get everything recorded inside the eight weeks. That entailed having two crews working round the clock – the second unit crew which would come on, which was awkward because we only had one set, so we couldn’t have two crews working at the same set at once. A second unit crew would have to log in when the main unit logged off, they were the night crew which came in and went on shooting, which meant that I could go on directing solidly for eight weeks without necessarily having to break for food and sleep, which was probably one of the major challenges because I also knew the more solidly one can work on it like that, the better it would be.

‘Because after eight weeks, it was a solid sort of total cut off, so it was a big incentive to burn the candle at both ends, and to just to keep going because you always knew that if you put in an extra five hours or something, you can make the movie that much better, and do a little bit more, so it was the biggest problem was getting through it without completely killing one’s self.

Everything gradually disintegrating towards the end and everyone getting more and more tired – the money running out, and the time running out (laughs). I guess one other major problem which was totally unforeseen was we went on location to the Sahara desert for one week, at the very end, which was sort of a special perk to try and get away from the fact that the rest of it was shot on one set, so we saved a bit of money to send off a skeleton crew to the Sahara to film a couple of extra scenes, to try and open the movie out.

‘And we had a freak flash flood of rain in the Sahara. That’s where they did shoot part of Lawrence Of Arabia and it was a sort of flash flood and rain, and many people in the area drowned, and it was declared a national disaster area, and the Moroccan cabinet drove by touring the disaster area and stuff.

‘Bertolucci’s people were down there filming The Sheltering Sky, it being a bigger movie, they all escaped through to Algeria, they were all at the same hotel, which meant that the desert scenes in Hardware are very rain lashed and kind of stormy, which is pretty good. It was just very hellish filming them, kind of trudging round the dunes, with all the camera gear on the back of a single hired camel on the dust road. Camels were a great way of moving camera gear to the top of the dune, and stuff which we would have had to carry. It was the rain and bad things which … the whole shoot got put off, it got shot in winter, eventually, which meant even the exterior shots in Britain are always totally covered in rain.

‘In the movie, we had to make it look like it never rained, and it was very hard. It was always tricky – and the Hardware street scenes are very thin because the weather at the time; if we were shooting it at summer, we could have had a lot more footage in the outside. It was just the fact of the rain outside stopped us from shooting. We spent a lot of days with the few exterior shots we got, like Lemmy and the river taxi and things, were usually sneaked, we would get like maybe two shots a day. We spent the rest of the time sitting around drinking coffee waiting for it to stop raining. All our exterior days were really lost in a way. The exterior footage in Hardware was really just what we could grab between showers and wind.

‘We had a lot more detail prepared ready to go which we couldn’t get in front of the camera. We didn’t have the time. There were a few bits and pieces – we were going to have a lot of dead cows being burnt in a pile as they walked past (Mo and Shades) and things like that. But they were all dropped because of lack of time. There was much more of the river-taxi landing scene, we had a bit of a “river-taxi other side of the city immigration area” worked out and built and ready to go, but it just rained solidly that day and we never got it together.

We asked Richard how he felt about his first feature in retrospect, and how he might have made some changes.

‘It would be hard for me to say the good points without beating my own drum, but I think the good points probably is that it’s pretty down beat and I think it takes a level headed look at what things might really be like in the future and that I do almost expect the world to be more like Hardware than Star Trek. I think the good points are that we made an attempt to try and not pull the punches and like at the end of the movie there’s no real way that they can save the world, or that the world will never get any better – you can’t do a sort of Total Recall – suddenly the atmosphere gets better and the sun comes out.

‘So the good point of it is that it’s probably … I don’t think it was tarting up the future or trying to make it out to be a good thing. I think Hardware rewards being watched by people who’ve seen a lot of other movies, in a way that I think that I was trying to cater to a late night video audience to an extent – people that might have watched some other movies that night. I think the bad points are that it was still quite heavily softened between the script and the release, and I figure at times that at times it’s too soft, particularly in the first half, in that all the characters teamed up, and I figure it could be – looking back to where we started from the original script some of the ideas we dropped – it’s quite sad that we didn’t keep it as hard as we wanted.

‘The Mo character should have been addicted to something bad, there was an idea in the original script that Jill was only keeping him in the flat because she was thinking of killing him and turning him into a work of art, and that’s as far as the relationship went in the original script. He was also a mechanic and a career military person in the script, with a drug problem and then that was cleaned up when Dylan McDermott came on board because Dylan McDermott arrived with a crew cut as a Christian, and the character had a lightning re-write into a career military person who read the bible. He changed from being a lot more of a psychobilly kind of character, when it was in the Bill Paxton phase. Those I think are the movie’s bad points in a way, and that I do think it could have done with a bit more roughness, and the sex scene also suffers because Dylan was just in that configuration – Dylan and Stacy, it wasn’t appropriate to make it any more outlandish. I would have preferred a more bio-mechanical sex scene – it could have been fun!’

And looking back, we asked, what might you have done differently?

‘In retrospect I would have liked to fight the Americans a bit more, and I would have liked to have stuck with the harder version of Hardware, to start off with. It’s just the small details all the way through, really. It’s in the original script, when Mo & Shades was walking across town, and Mo buys the droid from Alvy’s warehouse, Mo hires a bunch of street urchins, a couple of kids to carry the droid, and the scenes across the town, it’s always a bunch a snotty kids carrying the droid, and Mo has a big stick which he was knocking … he was hitting them with the stick that drew blood (all laugh).

‘Stuff like that in the script was all weeded out because the Americans would say “we can’t have the main character getting children to carry his bags, hitting them with the stick when they get tired” because that will make you not like him, and it’s just little things like that the whole way through – there was an old man being beaten up and robbed, and they walked past at one point as well, and it got dropped out of it because although it was just meant to be a bit of background street detail, like the baby tied to the dead man on the stairs.

‘It was dropped because they felt that having the main character walk past the old man being beaten up, and not doing anything about it, and working for the Government was not sympathetic to the main character, so we had to the whole way through prune little things like that, like Jill only apparently going out with him (Mo) because she’s able to tattoo him and she likes the scar tissue on his metal arm, and she’s like turning him into a work of art, but not because she has any interest in him otherwise.

‘All that kind of stuff got gradually dropped because it was too harsh, and the Americans were very concerned about having characters who the audience were usually going to like, you know, the sort of full of love – happy ending, kind of American ideal, so that was the thing I’d probably changed the most. I’d really like to have kept the security guard being mutilated. Alvy was all down to the limitation of the schedule – Alvy was originally killed in a much more horrible way. He was going to be pulled into a shredding machine. I really wanted to do a dwarf going into the shredding machine section. But that never happened. Various budgetary limitations again. People like Alvy and the security guard were too small to bother killing with elaborate detail.’

Stanley also seems genuinely impressed about the success his first feature got upon initial release. ‘Yeah, I was very surprised about the popularity because when we made it – we really thought it would be going direct to video, and have a very small, low profile kind of direct to video release, and wind up disappearing really fast. I was surprised initially when it come to the cinemas, and I was surprised when it opened as wide as it did. I think it opened in 700 cinemas on first release in America, and no-one’s sure how much money it’s made. It seemed to play and play. It went down very well in the Far East for some reason. I spoke to someone who’d been out in Korea, and the Far East and had seen it six times by accident! (all laugh)

‘It was playing as the in-flight movie which is a little hard to imagine, but I’ve got another friend who claims to have seen Wolfen as an in flight movie, complete with the severed hand and stuff. Strange things do show up in aeroplanes. It seems to have done very well. I think, that there was a figure of seventy million ($), a figure that it made world wide, and it comes up once every now and then, but no-one’s admitted to it, and no-one who has got points in the movie has ever seen any money out of it.

‘Yeah, I was very surprised at it doing well I figured that it would disappear much faster. It’s won a few odd trophies from film festivals as well. It won some kind of Jury prize at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival, purely because it was screened at the film festival on the same day that the Gulf War broke out, and Avoriaz is like a ski festival – all snow up in the Alps, so they were all coming out of the snow worrying about watching satellite television and seeing all these men with gas masks out in the desert, then sat down to Hardware with men in gas masks out in the desert, they took it very seriously.

‘In Europe and the foreign territories no-one ever laughs at Hardware; you don’t get people giggling the whole way through, and in the same way they think it’s a big statement on the way it has to be. So they gave us the big hunk of glass which is standing in the corner of the room. It was very hard to get home, to carry it back through a snow drift.’ (all laugh)

DUST DEVIL AND THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU

© Andrew Marc / Dickon Neech