by Andrew Marc

Jessica Palmer is a native of America (born in Oak Park, Illinois). She precluded her writing career with a much different occupational background. Having received her nursing degree in 1975, she went on to work at several hospitals in Kansas, all of which involved her in no doubt heavily emotional environments; intensive care, psychiatric unit, terminal cancer and detoxification unit. Maybe this was to later help form ideas for her horror writing.

In 1980, she was features writer for the Brazosport Facts (a daily newspaper in Brazoria Country), and in 1981, she reported for another daily, the Pasadena Citizen, Pasadena, Texas. Then Palmer made an unusual transition from journalism to technical writing. For just over three years, Jessica was technical writer for Schlumberger Well Services, Houston, Texas, and wrote such exotic manuals as Field Radiation Control, Radiation Sources and Control and Field Explosives Control. Then from 1979 to 1991 (the beginning of which over- lapped with her time at Schlumberger Well Services) she was manager of consulting firm Words, Et Cetera, latterly holding such a position in England.

A colourful and interesting background, and apparently not much scope for fiction writing, but almost surreptitiously, Jessica had been writing articles since 1979 (Salting It Away, August 1979 for the Salina Journal), perhaps in anticipation of a writing career, or perhaps because of the lack of formality and realism of her previous writing – “. . . it’s nice to be able to live so many different lives . . .” is a choice phrase which tells of the allure behind fiction writing. It wasn’t until 1990 that the fruits of her labour began to show, beginning with the publication of several short stories (Graven Images, March 1990, Fear magazine and The Gift, October 1990 issue of Cemetery Dance), and one year later, Jessica’s first novel, a horror called Dark Lullaby, was published by Pocket Books, New York. But there were quite a number of testing years prior to this when Dark Lullaby looked as if it would never see the light of day, so to speak. Jessica explains.

“The first publisher to buy it or be interested in it was Warner Communications . . . the editor who was interested in it left the company about the same time I was finishing the manuscript, and it just sort of fell through the cracks because no one else was interested in picking it up. The next publishers to actually buy it – this time I got a contract – were Paper Jacks, a Canadian based firm who had NY offices. They bought it and went bankrupt two months before it was due to be released. Then Pocket bought it after a two year long legal battle trying to get the rights back. So it was bought some six or seven years before it even saw the light of day.”

Sitting in an armchair in her modestly furnished lounge, Jessica looks almost bemused that her first novel ever made it to print. With her typical wry sense of humour, she qualifies the whole situation with a cynical adage: “I am the kiss of death as far as publishing is concerned.” The joy at finally having the book in the shops was unfortunately marred by the terms of contract with Pocket (US), namely the dreaded ‘non-competition’ clause, which basically means the publisher has you by the throat.

“. . . when Pocket (US) bought it (Dark Lullaby), they gave me a contract which said I could not write any full length, book length work, either fiction or non-fiction in any genre, in any name, in any Universe, in this life or any other life, until Dark Lullaby had been out six months.” She wasn’t allowed to sell, keeping her other book ideas reluctantly from the public, and having to make do with selling short stories (the latest of which, Full Moon Rising is due for publication through London Noir in June 1994), and very successfully (“. . . I’ve sold every short story I’ve ever written.”) “I kept doing other outlines . . . trying to get things out, trying to get things circulating. I did short stories because even though (they) don’t pay much, you get more reputability, the more often your name’s seen. So basically I did what every writer does and that’s struggle!”

After being demoralised by the constrictions of the contract surrounding her first book, Jessica arranged things in her favour. “Now, I learned my lesson with Dark Lullaby; with Cradle Song I told them ‘no way, you’re not going to sign me on this kind of contract’. It’s called the non-competition clause. In this country, as far as I know, it’s not legal, because that’s literally restraint of trade. If my trade is to sell horror novels, then to tell me I can’t do it is literally telling me that I can’t make my living . . . in the States it’s pretty much the standard. They buy you body and soul.” Palmer’s insistence on non restriction except in the horror genre slowed up contract negotiations by three or four months, but her stubbornness paid off. “I got it in the end. Literally I figured!”

“They buy you body and soul.”

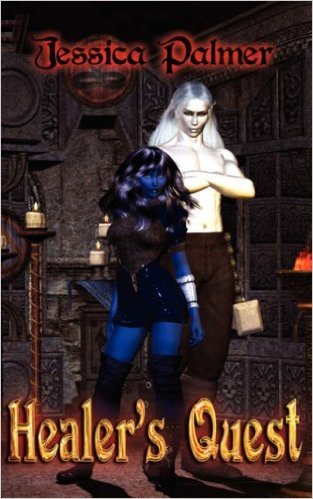

Her new found (or fought for!) artistic freedom was not put to use until 1993, when Jessica had her first fantasy novel, Healer’s Quest, the first in a series of five, published in Great Britain by Scholastic (under a new fantasy label for children, Point Fantasy). The same year, the sequel to her first horror novel was published in the US by Pocket Books, titled Cradlesong (this title will be in the UK next month, published by Simon and Schuster).

Once the ball was rolling, Palmer’s production rate became quite outstanding. Often working twelve hours a day, pounding away at her computer lurking away at the back of her flat, a focus for creativity, Jessica’s writing seems like an addiction. “I know that I out produce most writers. I don’t know whether I do as well in out producing most writers, I mean quantity does not necessarily mean quality. I like to believe that I give quality also, but I average three or four books a year – most writers average one. And that’s just because the ideas come boiling out of me.

“For me, writing is an adventure. I mean I’m having a blast . . . the fact that it happens so quickly, my biggest problem is that I can’t type fast enough. At the end of the day, it’s like ‘oh god, I’ve got to eat now!’ (laughs) ‘Will someone please pry my fingers off the keyboard?’” Having had her first novel nominated for the Horror Writers of America Bram Stoker’s award (and Healer’s Quest easily ranks alongside other top fantasy writers’ efforts), it appears that this particular writer has the exceptional talent of being able to produce quantity and quality.

“I definitely do an outline before I go for it. I have an overall idea that I want, and then I let the chapters evolve. For instance, Fire Wars; certain things in that book I hadn’t even thought of when I wrote the original outline, and these lovely characters like the imp named Pun just suddenly appeared. “I always know what the ending is going to be, and the adventure is figuring out how I’m going to get there.”

Writing, it seems, is somewhat of a game, to which every novelist has their particular rules. As an analogy, this seems appropriate for Jessica, who keeps describing her profession as “an adventure”, and in the way she constructs a novel. “You just know . . . the thought, if you will, and a chapter is sort of an elongated thought. You know when the thought is over, and I always try to leave my chapter in a special way.” A curious twinkle appears in Jessica’s eye, and knowing of her interest in Astrology and the arcane, as you might expect from a fantasy writer, I posed the question as to whether her subconscious plays a role in her creativity.

“Well, definitely my dreams get incorporated into my work . . . a lot of times you will find dream sequences in there (horror novels), and they’re actually dreams that I’ve had.”

Her plots are allowed to almost independently evolve as well. “I’ll be sitting there in, for lack of a better term, a meditative type state. I’m not thinking about my work at the time. And that’s when I come up with solutions for problems because you know any time you’re working on a manuscript problems start to happen. You think you have a nice straight line that you’re following and all of a sudden, you realise there’s a tangent; you’ve got the choice to follow the tangent or stay on the straight line.”

And after all this intense writing, head boiling with ideas and playing with fantastical figures one day, whilst giving life to sickening horror personalities the next, Jessica seems . . . not ordinary, but peculiarly well balanced. When we talk, not very much time elapses before some suppressed humour comes bubbling to the surface, almost like an antidote to the rigors of writing. With regards to the origin of plot ideas, Jessica jokes “. . . I kind of like the idea of a thousand chimpanzees on a thousand typewriters. That suits my sense of frivolity. When I get to be a big writer, when I grow up I’m going to hire me some chimpanzees. Or a secretary!”

You may have guessed that even after her huge workload, Palmer still finds time for extra-curricular activities, listing scuba diving , astrology and tarot as her main ‘hobbies’. The solitude of this profession must have an effect on most writers, and Jessica admits to being “. . . very nervous around people.”

“When you’re a writer, you’re quite literally playing god …”

And continues, “I think most writers are. You get so isolated in your own little world, and then all of a sudden you have to relate to another human being. When you’re a writer, you’re quite literally playing god, within the context of your story. You create the villains, you create the hero, you create the conflict, you create the illusion. You don’t have to interact with anything else, you have ultimate control over everything. And all of a sudden when you’re dealing with other human beings that aren’t nice and predictable like your characters, you suddenly think ‘Oh god, I’ve got to relate. I’ve got to make intelligent conversation. They’re going to say something to me, and I’m expected to respond appropriately. Oh shit!’

Recently, the public of Wealdstone recently had the chance to listen to her when she read some of her work at the local library, as part of national library week. She was joined by two other horror writers; Stella Hargreaves and Molly Brown (a fellow native of America). But until recently, Jessica had working hard on her last, Random Factor, a science fiction for Scholastic, which was used to promote the launch of their new S-F line.

Random Factor is about a war. “As a matter of fact it’s a rather cynical view of humanity. After the polar ice caps have melted, and all that remains in Europe is the Pennines . . . the Alps and a bunch of islands all over the place, and people live in bathospheres, because mankind tends to think of war as something which will help the economy. War has become the only economy; everything revolves – all society, all business – revolves around war. War has been moved to space because of course there’s no more land to do it on anymore. And they’ve (humans) gotten so cynical that they’ve even cloned a warrior class. And these people are two foot tall, because of course you don’t have to feed them much. In terms of creating space ships, you don’t have to make big spaceships.”

Set in an unspecific date in the future, with the action taking part in the local part of the galaxy (“We’ll be talking Mars, the Moon, not Andromeda.”), it sounds like an exciting new branch for this writer to tackle. On the lighter side of fiction, the humour (“. . . love the comedy”) – Jessica guises her jokes under the mystical veil of the fantasy genre. “Fire Wars really is (a comedy). I mean it’s fantasy, but there’s so many comical elements in it, it really is a kind of comedy.” But she points out that she is no Terry Pratchet imitator. “It was interesting because when I’d wrote Healer’s Quest. I’d never heard of Terry Pratchet. It’s just since I’d done that and started working on Fire Wars, someone said ‘oh, this is like Terry Pratchet’, then I started reading him. I’m not trying to be (his) imitator. If I have done it then it’s by accident rather than design.”

Jessica’s immense dedication to writing has been known to relegate normal, domestic necessities to almost an afterthought. “.…. I forget to eat. I will suddenly look at the watch and realise it’s ten o’clock at night and I haven’t eaten. I stop almost doing anything – I just write.” By virtue of this fact, a major talent is about to be properly recognised in the UK – Healer’s Quest is already the number one fantasy choice from libraries and schools across Britain. Remarkable indeed.

ANDREW MARC